Dying for fur - inside China's fur farms

SAP PC January 2, 2005, Fur China

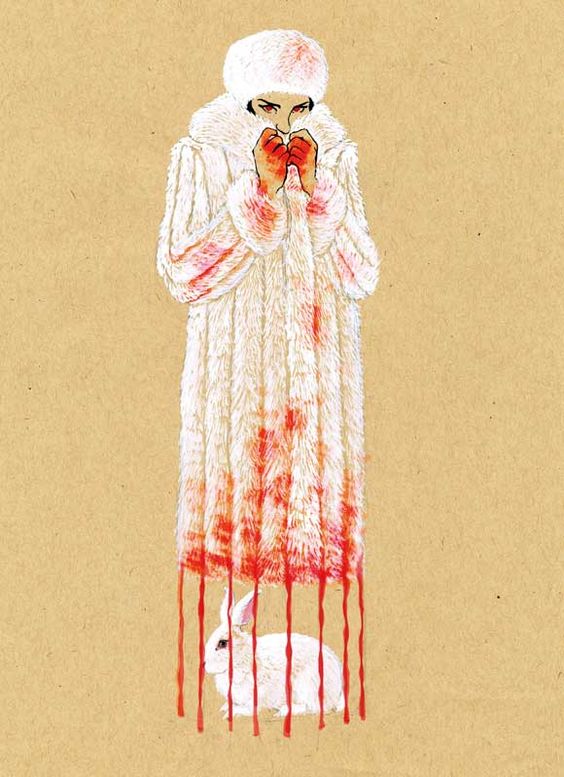

Merciless Slaughter: the unspeakable horror of China’s fur farms

Heinz Lienhard, President, Swiss Animal Protection (SAP)

Opening speech, SAP press launch 1st February 2005 Zurich, Switzerland

We may well be familiar with the conditions in Scandinavian and Eastern European ‘fur farms’ where hundreds of thousands of wild animals are kept in battery cages before meeting a brutal death in the name of fashion and vanity. Industry claims of “appropriate housing”, “good animal welfare laws in fur producing countries” and “happy animals, which generate glossy pelts” have long since been exposed as misleading whitewash. With the possible exception of some glamorous winter resorts, fur coats, capes and other pricy fur garments have all but vanished from the streets of Switzerland. Most people feel embarrassed to be seen in them. Others are unwilling to waste thousands of Swiss Francs on this type of phony luxury. There are, after all, endless ways of keeping warm and staying fashionable.

Nevertheless, fur is still big business. A string of commercial interests is cashing in, including breeders, fur farmers, exporters, importers, wholesalers, retailers, boutiques, department stores, and fashion houses. With fur sales flagging in the past, they have been busy searching for that all important new sales angle. And they found it: mass produced affordable fur garments for everyone. Fashion designers too have decided that fur trim is ‘chic’ and trendy. Instead of expensive full-length fur coats, fur now adorns anything from boots to parkas and coats – even children’s clothes don’t seem to be able to do without it. Fur has become a fashion fad!

Most of today’s ‘budget fur’, which appears as trim on hoods and as collars, originates from China, which dominates much of today’s market. It is estimated that China produces more than 1.5 million fox pelts a year and approximately the same number of raccoon dog pelts. Other common species ‘produced’ in China include mink, and even dogs and cats. China is literally swamping the international fur markets with its wares!

It comes as no surprise that, in defiance of the most basic animal welfare standards, the country’s millions of fur bearing animals are housed in the same scandalously cramped wire mesh cages that are customary in other fur producing countries. But until a few weeks ago, nobody knew the truth about how foxes and raccoon dogs on Chinese farm die. In collaboration with Asian animal protectionists, who used hidden cameras to document this gruesome business across the county’s far flung provinces, Swiss Animal Protection (SAP) today reveals a terrible truth. Joining forces with international conservation and animal welfare organisations, SAP will today, reveal the findings of this investigation to the world. The unspeakable horror we uncovered dwarfs everything we know about the nightmarish housing conditions and brutal killing methods employed in western fur ‘farms’.

By publicising these horrendous and deeply disturbing images from China, we want to make each and every member of the public aware of the truth behind the fur trim that decorates their collar or hood. The truth about how these animals were forced to live, and the way they had to die. This unspeakable disgrace has no place in a civilized world. If it is to end, the pubic needs to know the truth, so that decent and respectable people will no longer be willing to wear the products of such misery.

Our documentary concentrates on foxes and other wild animals. However, China also exports the skins of the companion animals we love and share our homes with. There is little doubt that these cats and dogs are kept under similarly dreadful conditions and die in the same barbaric fashion wild animals on fur farms are forced to endure. As part of talks concerning revisions of the Swiss Animal Protection Act, I personally asked the Swiss Minister of Economic Affairs, Josef Deiss, last year to at least prohibit the importation of dog and cat fur from China. Such a ban has already been introduced in many European countries and the USA. But my request fell on deaf ears. I will try to share this documentary with Minister Deiss and hope that he has the stomach to watch it.

Eighty thousand people have signed the petition against importing dog and cat fur from Asia. Swiss Animal Protection (SAP) deposited it in Bern, and National Councillor Dr. Paul Guenter will soon follow up with a parliamentary intervention. We will not rest until this abomination is banned from our country!

In closing, I would like to

salute the Asian investigators, who have obtained this footage by using

hidden cameras. They have accepted a great personal risk, and their lives

would be in jeopardy if their identities were to become known. To protect

them, even their voices had to altered in this documentary. Having to remain

anonymous, they will never gain the recognition or win the public accolades

they deserve. I would therefore like to take this opportunity to thank these

courageous individuals and express my admiration and respect for what they

did. Because we will never be able to thank them in person, I wanted to at

least use this opportunity to publicly acknowledge their contribution.

- A Report on the Fur Industry in China

- October 25, 2006 UPDATE

Hsieh-Yi , Yi-Chiao, Yu Fu, B.Maas, Mark Rissi

©

EAST International/Swiss Animal Protection SAP

SPEAK OUT AGAINST THE CRUEL FUR INDUSTRY

January 2005

Merciless Slaughter: the unspeakable horror of China’s fur farms Heinz Lienhard, President, Swiss Animal Protection (SAP)

We may well be familiar with the conditions in Scandinavian and Eastern European ‘fur farms’ where hundreds of thousands of wild animals are kept in battery cages before meeting a brutal death in the name of fashion and vanity. Industry claims of “appropriate housing”, “good animal welfare laws in fur producing countries” and “happy animals, which generate glossy pelts” have long since been exposed as misleading whitewash. With the possible exception of some glamorous winter resorts, fur coats, capes and other pricy fur garments have all but vanished from the streets of Switzerland. Most people feel embarrassed to be seen in them. Others are unwilling to waste thousands of Swiss Francs on this type of phony luxury. There are, after all, endless ways of keeping warm and staying fashionable.

Nevertheless, fur is still big business. A string of commercial interests is cashing in, including breeders, fur farmers, exporters, importers, wholesalers, retailers, boutiques, department stores, and fashion houses. With fur sales flagging in the past, they have been busy searching for that all important new sales angle. And they found it: mass produced affordable fur garments for everyone. Fashion designers too have decided that fur trim is ‘chic’ and trendy. Instead of expensive full-length fur coats, fur now adorns anything from boots to parkas and coats – even children’s clothes don’t seem to be able to do without it. Fur has become a fashion fad!

Most of today’s ‘budget fur’, which appears as trim on hoods and as collars, originates from China, which dominates much of today’s market. It is estimated that China produces 4 million fox pelts in 2006 and approximately the same number of raccoon dog pelts. China’s estimated production of mink pelts is approximately 10 million which represents a 25% increase over last year’s estimate. Other common species ‘produced’ in China include even dogs and cats. China is literally swamping the international fur markets with its wares!

It comes as no surprise that, in defiance of the most basic animal welfare standards, the country’s millions of fur bearing animals are housed in the same scandalously cramped wire mesh cages that are customary in other fur producing countries. But until a few weeks ago, nobody knew the truth about how foxes and raccoon dogs on Chinese farm die. In collaboration with Asian animal protectionists, who documented this gruesome business across the county’s far flung provinces, Swiss Animal Protection (SAP) produced a video which reveals a terrible truth. Joining forces with international conservation and animal welfare organisations, SAP adds the findings of this investigation to the world wide campaign against fur. The unspeakable horror we uncovered dwarfs everything we know about the nightmarish housing conditions and brutal killing methods employed in western fur ‘farms’.

By publicising these horrendous and deeply disturbing images from China, we want to make each and every member of the public aware of the truth behind the fur trim that decorates their collar or hood. The truth about how these animals were forced to live, and the way they had to die. This unspeakable disgrace has no place in a civilized world. If it is to end, the pubic needs to know the truth, so that decent and respectable people will no longer be willing to wear the products of such misery.

Our documentary concentrates on foxes and other wild animals. However, China also exports the skins of the companion animals we love and share our homes with. There is little doubt that these cats and dogs are kept under similarly dreadful conditions and die in the same barbaric fashion wild animals on fur farms are forced to endure. Under the impression of our video documentation the Swiss Parliament voted in December 05 to ban the import of cat and dog fur.

In closing, I would like to thank the Asian investigators, who have obtained this footage. They have accepted a great personal risk, and their lives would be in jeopardy if their identities were to become known. To protect them, even their voices had to altered in this documentary. Having to remain anonymous, they will never gain the recognition or win the public accolades they deserve. I would therefore like to take this opportunity to thank these courageous individuals and express my admiration and respect for what they did. Because we will never be able to thank them in person, I wanted to at least use this opportunity to publicly acknowledge their contribution. Heinz Lienhard

Executive Summary:

This is the first ever report from inside China’s fur farms. Investigators of the organisations Swiss Animal Protection SAP and East International visited several farms in Hebei Province as part of this field research. Numbers of animals held at these facilities ranged from 50 to 6000. The report is based on field and desk research carried out in 2004 and January 2005. It provides background information on the Chinese fur industry and describes and documents husbandry and slaughter practices. The report goes on to place China’s role as the world’s largest exporter of fur garments into a global context, which involves direct links to Europe and the United States. It ends in a set of urgent recommendations for policy makers, retailers, fashion designers and consumers.

For at least ten years, the international fur industry has waged a coordinated, well funded and slick global PR campaign aimed at dispelling the moral stigma attached to wearing fur. Mixing fur with silk, wool, suede and leather, employing new manufacturing processes such as shearing and knitting, as well as new fashionable colours, have added novelty and versatility to fur. Steadily increasing marketing of fur accessories and clothing and footwear with fur trim (e.g. collars, scarves or on hoods) has almost imperceptibly brought fur back out onto the streets. Targeting a younger and fashion conscious market, fur is now included in anything from evening wear to sports wear, haute couture to ready-to-wear mass produced affordable garments.

Eighty five percent of the world’s fur originates from farms. China, also a member of the International Fur Trade Federation (IFTF), is the world’s largest exporter of fur clothing and according to industry sources, the biggest fur trade production and processing base in the world.

Between 25% and 30% of the country’s fur is obtained from wild animals, while 70-75% originate from captive animals. China is also one of the few countries in the world without any legal provisions for animal welfare.

Most Chinese fur farms were established during the past ten years. Wild species bred for fur include red and arctic foxes, raccoon dogs, mink, and Rex Rabbits. A growing number of international fur traders, processors and fashion designers have gradually shifted their business to China, where cheap labour and the absence of restrictive regulations make life easier and profit margins broader.

To date, Chinese fur farmers hold four million foxes and an estimated four million raccoon dogs. The Sandy Parker Report estimates Chinese mink production to be in the neighbourhood of ten million and growing rapidly (issue 16 October, 2006). China is now the world’s leading producer of fox and raccoon dog pelts and the second largest producer of mink pelts

The international fur sector is complex, with pelts produced by farmers passing through several countries and undergoing various processes before it reaches the final consumer.

Chinese Customs statistics indicate a net volume of fur imports of US$ 330 million (China Daily 04-08-2005) and exports of nearly US$ 2 billion for 2004. Zhang Shuhua, deputy chairman of the China Leather Industry Association told reporters that the fur imports were up 54 % and exports 123 % (!) within one year from 2003. More than 95% of fur clothing produced in China is sold to overseas markets, with 80% of fur exports from Hong Kong destined for Europe, the USA and Japan. According to the Sandy Parker Report (3/21/05) China exported a staggering US$ 1.2 million in fur trimmings to the United States just in the month of January 05. The country’s expanding product range includes pelts, full coats, fur accessories, such as scarves and hats etc., toys, garment trimmings and even furniture. A random market survey in boutiques and department stores in Switzerland and London discovered fur garments labelled “Made in China” among top fashion brands.

In Switzerland and several other European countries, fur farming has been banned on animal welfare grounds. In all farms visited in China, animals were handled roughly and were confined to rows of inappropriate, small wire cages, which fall way short of EU regulations. Signs of extreme anxiety and pathological behaviours were prominent throughout. Other indicators of poor welfare include high cub mortality and infanticide.

Between November and March, foxes and raccoon dogs are sold, slaughtered, skinned and their fur is processed. Animals are often slaughtered adjacent to wholesale markets, where farmers bring their animals for trade and large companies come to buy stocks. To get there, animals are often transported over large distances and under horrendous conditions before being slaughtered. They are stunned with repeated blows to the head or swung against the ground. Skinning begins with a knife at the rear of the belly whilst the animal is hung up-side-down by its hind legs from a hook. A significant number of animals remain fully conscious during this process. Supremely helpless, they struggle and try to fight back to the very end. Even after their skin has been stripped off breathing, heart beat, directional body and eyelid movements were evident for 5 to 10 minutes.

This report shows that China’s colossal fur industry routinely subjects animals to housing, husbandry, transport and slaughter practices that are unacceptable from a veterinary, animal welfare and moral point of view. Housing, husbandry, transport and slaughter conditions fall drastically short of both Swiss and EU legislation.

We therefore urgently appeal to:

- Chinese government to pass a national animal welfare law.

- Chinese government to urgently introduce and enforce legislation prohibiting the skinning of live animals.

- Chinese government to urgently introduce and enforce legislation prohibiting inhumane treatment and slaughter methods

- Chinese government to introduce and enforce legislation prohibiting the inhumane confinement of animals

- Fashion designers to shun the use of fur in their collections and use non-violent materials instead

- Shoppers not to buy fur garments or accessories or clothes with fur trimmings

- Shoppers to check whether designers incorporate fur in their collections

- Fashion retailers not to stock garments or accessories or clothes with fur trimmings

(A comprehensive selection of photographs and video footage are available (© SAP).

Fur farming in China

Commercial fox farming in China began in 1860. As fur farming expanded into a major industry in the West, China began to follow suit by the mid 1950s. From 1956, breeding foxes for fur became more widespread. At the time some 200,000 foxes were added to the country’s fur farms each year. Collectively they churned out more than a million skins a year. As China began to open up commercially between the 1980s and 90s, the country’s fur industry boomed. Next to traditional state-run farms, numerous private and family run farms started to spring up. During the 1990s, the sector attracted foreign investments, which lead to the establishment of even more fur farms. To date, Chinese fur farmers hold four million foxes and an estimated four million raccoon dogs and ten mink s and the production is growing rapidly. China is now the world’s leading producer of fox and raccoon dog pelts and the second largest producer of mink pelts

Many farms are facing inbreeding related problems, which lead to a gradually deterioration of fur quality. In 2005-06 Finish fur breeders exported 10'000 foxes to China for breeding purposes. Many of the foxes did not survive the ordeal of the long travel. Heilongjiang Province has also seen the establishment of a fox farm which specialises solely in breeding. One farm owner stated that similar enterprises are soon to be initiated in Hebei as well. Other fur related business ventures include the sale of Finnish blue fox sperm and instruction in artificial insemination techniques.

The expansion of the mink production in recent years has been based mostly on breeding stock acquired in North America and Europe.

Fur markets and trade centres continue to mushroom, accompanied by an upsurge of companies dealing in all manner of fur, pelts, trimmings, garments and other relevant products and services.

Major farming areas

According to Chinese industry sources, fur farms in Shandong Province, situated in the country’s North-East, hold the highest number of animals, including more than 1’500,000 foxes. Next up is Heilongjiang Province, where over 500,000 foxes are held for their fur. The number of foxes on farms in Jilin Province too exceeds the 500,000 mark and continues to rise.

While fur farms are also present in Hebei Province, this part of China primarily acts as one of the country’s main hubs for wholesale and retail markets. Some of the animals bred in Shangdong Province are sold and transported to Hebei to be slaughtered and skinned. Liou Shih in Li County and Shangcun in Suning County, both in Hebei Province, are China’s biggest fur wholesale and retail markets. Liou Shih market deals mainly in raw cow hides and sheep skins, commonly known as “rough fur”, while the market in Shangcuen specialises in mink, fox, Rex Rabbits and raccoon dog skins, collectively referred to as “fine fur”.

At the Shangcun market 35 million pieces of fur are traded each year. This accounts to over 60% of China’s pelt trade. Shangcun is dubbed the "Fur Capitol“. Suning county has 152 sizable fur farms, 65 villages that specialise in fur production with around 10'000 farmers owning a total stock of 470'000 raccoon dogs, foxes and mink. According to Suning county’s Party Committee’s Propaganda Department around 50'000 of the 330'000 inhabitants are employed in fur-related jobs.

China is a member of the International fur Trade Federation IFTF

„Fur farming is well regulated and operates within the highest standards of care“ according to the International Fur Trade Federation IFTF. China is a member of this Federation. On Chinese fur farms, foxes raccoon dogs are confined in rows of wire mesh cages (3.5x4cm mesh) measuring around 90(L) x 70(W) x 60(H) cm. The cages are raised off the ground by 40–50cm. They contain no furnishings, no toys, no things to gnaw, no plateaus nor nest boxes, and in many cases, no roof. Each wire mesh cage houses one or two animals. Cages housing breeding females link to brick enclosures intended to offer females a degree of seclusion during birth and cub rearing to reduce cub mortality, e.g., through infanticide or maternal neglect (see below under ‚cub mortality’).

Fur “farming”

Mating takes place from January to April. The majority of farms use artificial insemination, especially to cross-breed blue and silver foxes, whose mating periods do not coincide. Foxes reach sexual maturity after 10-11 months. Breeding animals are used for five to seven years. Farm owners state that vixens produce average litters of 10-15 cubs a year between May and June. Cubs are born in spring and weaned after three months. According to farm owners, average cubs survival rate is 50% to weaning. This means that farmers gain around five to seven cubs per litter. Cubs are usually slaughtered after a further six to eight months, after they have undergone their first winter molt. Farmers retain some animals as breeding stock, but most animals are sold at the end of each year.

Red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) weigh 5.2-5.9kg with a head-body length of 66–68cm. Arctic foxes (Alopex lagopus) have a head-body length of 53-55cm and an average body weight of 3.1-3.8kg. Raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides), an Asian fox-like canid, weigh between 2.5 and 6.25kg with an average body length of 56.7cm in Japan, and 51 .5-70.5cm and 3.1-12.4kg for Finnish raccoon dogs (Kauhala K & Saeki M, 2004).

Pathological behaviours, which indicate significant welfare problems, such as extreme stereotypic behaviour, severe fearfulness, learned helplessness (unresponsiveness and extreme inactivity) and self mutilation, were observed and documented on all farms. Farmers also reported breeding difficulties and infanticide, which have also been associated with poor welfare in these and other species.

When farmers handle foxes they remove them from their cage with iron tongs which they clamp around the neck. Then they grab them by the tail. Two types of tongs are used. Subsequent handling usually involves holding the animals upside down by their hind legs.

The rearing season extends from June to December. Once animals are selected for fur production as opposed to breeding, the quality of their fur is the farmers’ sole concern. Before animals are ready for slaughter, farmers examine the maturity and quality of their fur. Between November and March, foxes and raccoon dogs are sold, slaughtered, skinned and their fur is processed.

Behavioural Problems

Behavioural Problems

When individuals are placed into artificial environments, both the complexity and amount of their physical surroundings are dramatically reduced. In addition, captive animals are forced to tolerate and closely interact with humans, who control every aspect of their daily lives (Carlstead K. l996: „Effects of captivity on behaviour of wild mammals“) In the wild, animals can control stimulus loads by making behavioural adjustments, such as approach, attack, chase, explore, avoid or hide. In a dramatic 'reality shift', these coping strategies are n longer available in most captive situations. Lack of control and exposure to inescapable adversity is recognised as profoundly damaging, and it has therefore been argued that many chronic stressors are unique to captive environments.

Professor Donald Broom of the Veterinary Department of Cambridge University argues that behavioural abnormalities are best suited for the detection of chronic welfare problems (Broom D. & Johnson K. l993 „Stress and Animal welfare“). Where they occur they are usually associated with the absence of 'resources' the animal requires and corresponding frustration. This can mean anything from access to more space, a more stimulating or quiet environment, the ability to perform certain behaviours and access to social or sexual partners.

In Chinese fur farms, foxes, raccoon dogs, mink and rabbits are confined to narrow wire mesh cages.

The Swiss regulations stipulate, that two foxes must be given an outdoor area of at least 30 m2 and an indoor area of 8 m2. Natural ground for digging, sleeping boxes and hiding places are mandatory. Two mink are entitled to at least 6 m2 plus an ability to swim. Two raccoon dogs are must be given an outdoor area of at least 30 m2, an indoor area 8 m2, natural ground and hiding places. These are the minimum requirements according to Swiss regulations. European guidelines stated in the Council of Europe's 'Standing Committee of the European Convention for the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes, Recommendation Concerning Fur Animals on fur animals' stipulate a minimum cage area for foxes on fur farms of 0.8m2 or 8000cm2. Some of the larger cages holding foxes and raccoon dogs in China measured around 90 x 70cm, the equivalent of 0.63m2 or 6300cm2. Thus, even in the larger cages in China, foxes and raccoon dogs have a third less floor space and 14% (10cm) less cage height then minimum EC recommendations.

Farmed foxes are known to suffer from extreme fear (see Broom 1998/ Wipkema l994), which is exacerbated by the close proximity of humans, frequent and rough handling, inability to withdraw and crowded housing near other foxes. According to Council of Europe recommendations adopted by the Standing Committee on 22 June 1999, foxes should therefore be supplied with year-round nest boxes. However, in addition to being confined in unsuitably small and bare cages, foxes on Chinese fur farms have been denied this. Fear has been linked to physiological stress, the development of abnormal behaviours (see below), infanticide in nursing mothers and - not surprisingly - poor welfare. All are widespread on Chinese fur farms, as were signs of self-mutilation. In addition to excessive fear, research has identified the barrenness of cages and impaired reproduction as major problems associated with fox farming. Their presence too, has therefore been associated with poor welfare in this species. In recognition of these factors, apart from Switzerland, several European countries such as Austria, England, Holland and Sweden have banned or severely restricted fox farming. EU recommendations also stipulate that "until there is sufficient information on the welfare of raccoon dogs, keeping of this species on fur farms should be discouraged." (adopted 0n 12-13 Dec. 2001).

Caged animals often perform repetitive, behaviour patterns, known as stereotypes. Stereotypes are repetitive, invariant behaviour patterns that serve no apparent function. These behaviours are frequently seen in captive animals, and in carnivores typically take the form of pacing back and forth. In some cases, pacing may be accompanied by, or consist solely of other repetitive movements, such as a nodding or circling of the head - a common sight in farmed mink. These patterns were extensively documented by the investigators.

Other foxes on the Chinese fur farms were often inactive and apathetic, sometimes having retreated to the backs of their cages. Ongoing uncontrollable aversive stimulation can lead to a behavioural response termed 'learned helplessness' (Seligman M, l975 ‚Helplessness’), which at first glance can appear similar to habituation (Freeman B.M.& Manning l979 „Stressor Effects of Handling in the Immature Fowl“). However, the behavioural sign of 'giving up' in the face of uncontrollable aversive conditions is linked to profound physiological effects (Fox M.W. l984 "Husbandry, Behaviour and Veterinary Practice“) associated with poor welfare.

Scale of farming operations

Small fur farms are often run as family businesses. Mid-size farms retain between 10 and 15 workers, while larger facilities employ from fifty to several hundred farm hands. Farms and fur trade related businesses in Shangdon and Heilongjiang Provinces are the biggest and most efficient in China. With animal numbers ranging from 1,000 to more than 10,000 per farm, many have been the recipients of overseas investments. One of the largest farms holds more than

15,000 foxes and 6,000 mink. (Chinese Alibaba Information Website, Nov.04) Operating as a multi-functional enterprise, it incorporates artificial insemination, breeding, slaughtering, pelt-processing, tanning, and post-production facilities. It is also engaged in export to other countries.

In Hebei Province, many fox farms have set up shop in the vicinity of cities and towns such as Tanshang City, Laoting County, Li County, Bao Shu City, Shangcun or Xinji county The majority of these farms are run by private individuals. Animals generally number from under one hundred to several hundreds. The biggest farm in this province holds more than 20,000 animals. (China Consumer Website) Smaller farms focus mainly on breeding and then sell their foxes to wholesale markets or slaughter houses. Skins are then passed to the next tier of fur traders and processors for further treatment and post-production.

Several farms in Hebei Province were visited as part of the field research for this report. Numbers of animals held at these facilities ranged from 50 to 6000. Some farms mainly keep foxes, but the majority also hold other species such as mink, raccoon dogs, and Rex rabbits.

- Fox species commonly kept include different colour morphs of arctic (Alopex lagopus) (white and blue fox) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) (red and silver fox). Fur farmers are said to mostly use it to crossbreed blue and silver foxes, as their natural mating periods do not coincide. Industry figures estimate that China produces around 10 million mink and 4 million fox skins each year – the equivalent of 30 % of the world’s mink and 60 % of the world’s fox production

Slaughter methods

Animals are slaughtered adjacent to wholesale markets, where farmers bring their animals for trade and large companies come to buy stock. To get there, animals are often transported over large distances and under terrible conditions before being slaughtered.

A metal or wooden stick is used to repeatedly strike the heads of foxes, raccoon dogs or mink while they are held by their hind legs. Alternatively, workers may grab the animal’s hind legs and swing its head against the ground. The animals struggle or convulse and lie trembling or barely moving on the ground. The worker then stands by to watch whether the animal remains more or less immobile. These hands-on methods are intended to stun the animal

Many, whilst immobile, remain alive. Skinning begins with a knife at the rear of the belly whilst the animal is hung up-side-down by its hind legs from a hook. In some cases, this took place next to a truck which collected the carcasses – for human consumption. Starting from the hind legs, workers then wrench the animals’ skin from their suspended bodies, until it comes off over the head. The investigators observed and documented that a significant number of animals remain fully conscious during the procedure.

Helpless, they struggle and try to fight back to the very end. Even after their skin has been stripped off breathing, heart beat, directional body and eyelid movements were evident for 5 to 10 minutes. They struggle, trying to defend themselves to the very end. Even after their skin has been stripped off breathing, heartbeat, directional body and eyelid movements were evident for up to five to ten minutes.

On numerous occasions, animals that had been stunned initially, regained consciousness during the skinning process and started to twist and move around. Workers used the handle of the knife to beat the animals’ head repeatedly until they became motionless once again. Other workers stepped on the animals’ head or neck to strangle it or hold it down.

Guo Wanyi, Vice-Head of Suning County claimed on 8 April 05 in the government owned newspaper China Daily which is published in English, that the local government has banned the brutal slaughter practises. According to a local regulations passed on 1 September 2003 by Cangzhou city, the suggested methods for killing foxes apparently include injection by drugs, intercardiac injection of air and electrocution.

Observations confirmed by Chinese journalists

The shocking observation of the SAP/East International investigators was confirmed by journalists of the newspaper Beijing News (a newspaper jointly operated by Beijing Daily and South Daily, circulation 500'000) on 5 April 05. In a lengthy article they describe what they saw on 21 March 2005 at the fur market of Shangcun town. "Once pulled out from its cage, the raccoon dog curls up into a bal in mid-air. A few middle-aged women carrying wooden clubs gather round. One woman in a headscarf is first to grab hold of the raccoon dog's tail and the others drift away peevishly. The woman in the headscarf swings the animal upwards. It forms an arc in the air and is then slammed heavily to the ground, throwing up a cloud of dust. The raccoon dog tries to stand up, its paws scrabbling in the grit. The wooden club in the woman's hand swings down onto its forehead. The woman picks up the animal and walks towards the other side of road, throwing it onto a pile of other raccoon dogs. A stream of blood trickles from its muzzle, but its eyes are open and it continues to repeatedly blink, move its paws, raise its head and collapse to the ground. Beside it lies another raccoon dog. Its four limbs have been hacked off but still it continues to yelp. Ten or more minutes later Qin Lao approaches the raccoon dog with a knife. His job is to skin the animals. The raccoon dog is suspended upside down from a hook on the overhead bar of a motor-tricycle and the area around the hind legs and anus is scored with the knife. There is a ripping sound as the skin is torn completely from the hind legs and the animal struggles to turn away, crying out. The skin is ripped up to the abdomen. Qin Lao's body is bent with effort like a bow at full stretch, but the fur remains stubbornly attached to the flesh. A middle-aged woman jogs over to help, and their backs arched with the strain. The whole fur is finally ripped from the raccoon dog's body. The animal is thrown onto the back of the truck, steam rising from its blood-red body. It tries to stand up again, lifting its head and glancing down at its own body. Without blinking it tries once more to turn its head and then falls still. 'Skinning the animal dead or alive is all the same, but it is more convenient and neater this way. Everyone has always done it like this', explains Qin Lao.“

Prying eyes not welcome in China. Late 2005 this was also experienced by journalist Dominic Waghorn from the Beijing office of Sky News. He was greeted with a less than warm welcome when he and his producer investigated the Beijing fur industry. He reported that Instead of being clubbed to death, the animals are electrocuted with home-made devices wired to tractor batteries. They struggle to escape as one prong goes in their mouth, the other in their anus, then lie twitching and whimpering on the ground. Often the voltage isn't strong enough. There is no effort to check they are dead before they are strung up on the tractor and skinned. In the back of the vehicle their skinless bodies pile up, some clearly still alive, their hearts still beating.

On January 12, 2006 Wang Wie, Deputy Director of Department of Wildlife Conservation Under State Forestry Administration was the first high official to acknowledge problems in the fur production. He stated in a speech:" In the early 2005, when we were informed about the non-standard skin-taking approach such as “peeling off marten alive” in Suning County of Hebei Province, we were shocked and immediately made initial investigation on that event and the general situation of the fur-bearing wildlife breeding and utilization nationwide, in a joint effort with China Leather Association and China Wildlife Conservation Association. According to the findings of the investigation, the behavior of “skinning marten alive” in Suning County of Hebei Province would be no good to the fur quality to adopt the approach of “skinning alive,” which increases the difficulty and inevitably lower the efficiency of skin-taking. Obviously, “skinning alive” is impossible as a common approach of the industry. From the above-mentioned cases and our follow-up investigations, we recognized that there are still circumstances of poor breeding conditions, lagged-behind breeding techniques, and non-standard approach of killing and skinning fur-bearing animals in the industry.“

Environmental hazards

The sheer scale in numbers of animals killed in and around the major fur processing centres poses a considerable environmental burden. Enormous amounts of blood and offal accumulate in these open-air slaughter facilities.

The same applies to tanneries, where dangerous chemicals, including chromium, represent an additional health and environmental hazard. According to Professor Cheng Fengxia of Shaanxi University of Science and Technology, “Pollution caused by inappropriate processing, especially colouring the fur, has become a headache”. (China Business Weekly 20 Jan.04)

At markets in Haining in Zhejiang Province for example, nearly 100,000 pelts are traded each and every day. They are then treated, processed, coloured, trimmed or woven to match the fashion tastes of the day.

China is the world’s leading producer of fur garments. Added to its domestic production of fur, China imports five million mink pelts and 1.5 million fox pelts each year (China Business Weekly 20 Jan. 04). This amounts to 40% of the world’s fur auction house transactions. Many of these pelts are dyed in China The fashionably coloured fur trimmings are then re-exported. In 2002/03, 40 percent of the fox pelts produced in Finland (845,325 pieces) were exported to China and Hong Kong. Thirty-eight percent of the Finish mink production too was exported to China (1,633,682 mink pelts).

Lack of trade transparency

The international fur sector is complex, with pelts produced by farmers passing through several countries and undergoing various processes before reaching the final consumer (EFBA/IFTF 2004:efbanet.com/economics.htm) The IFTF recognises China as the world’s largest exporter of fur. China has expanded its own production to such an extent, that most of the fox furs at the auction houses of Helsinki and Kopenhagen could not be sold. The buyers from China and Hongkong stayed away. On the other hand, in spring 2005 China has started to sell their own pelts at the Helsinki and the Copenhagen fur auctions.

More than 95% of fur clothing produced in China is sold to overseas markets, including Europe, the USA, Japan, Korea and Russia, with 80% of fur exports from Hong Kong destined for Europe, the USA and Japan. Products include fur, fur garments and fabric or leather garments with fur trim. China has also become the leading fur garment exporter to the US, accounting for 40% of total US fur imports in 2004 – the equivalent of US$7.9 million (Melbourne Paper January 10, 2005 page 15 “Coats selling fast, that’s fur sure”). Exact export statistics, however, are difficult to obtain as fur trimmings are not specifically declared to customs. Furthermore, retailers can import stock which is then re-exported to another country.

Most retailers are unwilling to declare the true origin of their garments in an effort to avoid the image of cheap production and inferior quality. Any fashion retailer can import from China without having to declare the origin when reselling the merchandise. If is mentioned at all, the final label may only read e.g. “Made in Italy” or “Made in France”. Most retailers do not even identify the type of fur used for trimmings. However a random market survey in boutiques and department stores in Switzerland, London and New York discovered fur garments labelled “Made in China” among top fashion brands. The video of the market survey conducted and aired by Swiss National Television SF DRS on 1 February 2005 can be viewed online at Internationally, the overall economic importance of the classic furrier has become greatly diminished during the past ten years. In many countries, their relative contribution to revenue generated from fur garments sales has become all but irrelevant. Sandy Parker Report stated that “traditional furriers must recognise that a share of at least their potential market has now been taken away by non-fur retailers. Thus, while their own sales may have remained steady or increased marginally, furs sold by department and specialty stores, including boutiques, are up substantially and may account for the bulk of the increases that were registered in the past two years. Similarly, any decline in sales by fur stores and departments may not necessarily signify a general decline in demand for fur, but possibly that fur customers are finding what they want elsewhere“. (Sandy Parker Report, January 10, 2005)

Non-existence of a national animal welfare law

Both the Environment Protection Law and the Wildlife Protection Law - the two most important laws concerned with animals in China- cover the protection of wildlife in the wild. Wild animals in captivity are treated as resources and properties, in the form of objects. There are no acts banning cruelty in the Chinese legal system (Song Wei, Professor, Law Institute, University Hefei, CIWF Conference 18 March 05 „China’s Approach to Animal Welfare Law“). A number of well publicised incidents of animal cruelty have exposed the lack of legal protection for captive animals in China. In February 2002, a student poured concentrated acid onto bears in Beijing Zoo. The offender went free. The public outrage surrounding the plight of bears and the handling of the offender sparked a national debate on the need for anti-cruelty legislation (Paul Littlefair, RSPCA Internat. Deptmt, 2005 CIWF-Conference: „Why China is Waking Up to Animal Welfare"). This contrasts with the bold assertion by the Chinese Fur Commission in a letter to Swiss Animal Protection dated 7 March 05. It states that Chinese fur animal farms are under joint administration of China’s State forestry administration and Ministry of Agriculture. Rules and regulations related to fur animal farming include the Wild Animal Protection Law and the Regulations for the Protection of Terrestrial Wildlife and Management Procedures on License for Domestication and Breeding of Wildlife under special State Protection. Little surprise that the China Fur Commission wrote „Furthermore we doubt some viewpoints and material of the (SAP/East-International) report to be invented or exaggerated“. Some counties claim to have passed regulations on fur farming, but up to now, nobody has been sentenced for infractions.

Is fur quality a welfare indicator?

In one of its perennial arguments in defence of fur farming, the industry claims that fur quality is a sure fire indicator that animals are well cared for. Statements like, "It is a fact that fur farming and good welfare go hand in hand." may sound sensible, but it's not that simple. Foxes and mink are killed after their first winter molt, when their coat is in prime condition. Years of selective breeding for fur quality have produced animals, whose fur quality is less sensitive to welfare conditions than, say companion animals. In its report on the welfare of animals farmed for fur, the Scientific Committee on Animal Welfare Health and Animal Welfare of the European Commission states (page 73): "Fur clarity and density do not correlate with any other welfare measure. Thus, except in extreme cases indicative of pre-clinical or clinical conditions, or cases of pelt biting, mink pelt condition is probably best considered a production measure rather than a sensitive welfare measure."

- Cub Mortality

Infanticide is a familiar problem on fox farms. According to fur farm owners in China, average cub mortality to weaning is a mere 50%. This is exceptionally high even for foxes on farms. In Sweden an estimated 15-30% of fox cubs die before weaning and in Finland, the fur trade magazine 'Turkistalous' mentions estimated 30% mortality in 1990 . A Norwegian study referred to in European Commission in its report The Welfare of Animals kept for Fur Production, describes cub mortality levels of 16.8% for silver foxes and 22% for red foxes (Den Norske Pelsdyrkontroll 1999).

Conclusion:

Conditions on Chinese fur farms make a mockery of the most elementary animal welfare standards. In their lives and their unspeakable deaths, these animals have been denied even the most simple acts of kindness. Instead, millions of individuals are forced to endure the most profound indifference to their suffering and most basic needs – in the name of fashion. This report shows that China’s colossal fur industry routinely subjects animals to housing, husbandry, transport and slaughter practices that are unacceptable from a veterinary, animal welfare and moral point of view.

November 22, 2017 Donkeys bludgeoned with sledgehammers, slaughtered and skinned for horror Chinese medicine trade ‘SLOW, AGONISING DEATH’

Animal Rights Groups Taking action for the voiceless. Be part of the movement!