Is pet overpopulation a myth? Inside Nathan Winograd's

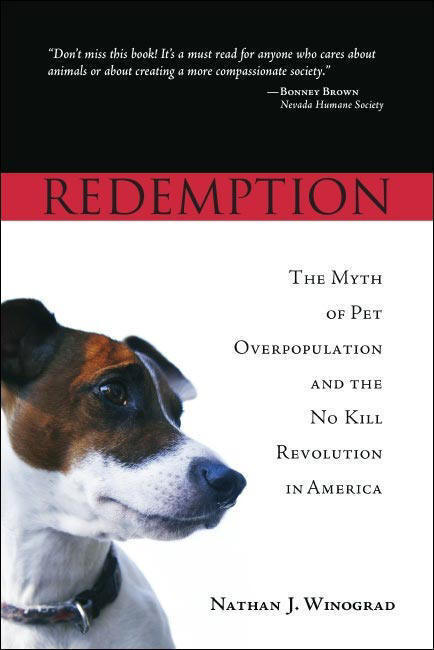

"Redemption"

- Tuesday, October 2, 2007

- By Christie Keith, Special to SF Gate

In the still-heated debate over reducing shelters deaths in California, there is probably no more polarizing figure than Nathan Winograd, former director of operations for the San Francisco SPCA.

At first glance, Winograd has all the credentials any animal rights activist or shelter professional could ask for. He's a vegan. He left a lucrative career as a prosecuting attorney to devote himself to helping animals. Last year, his income was only $35,000. He has spearheaded the No Kill Advocacy Center, a national organization aimed at ending the killing of pets in animal shelters. While director of operations at the San Francisco SPCA, he worked with then-president Richard Avanzino to implement a wide variety of animal livesaving programs, and then went on to achieve similar success as director of a rural shelter in upstate New York.

But Winograd isn't making a lot of friends in the shelter industry these days. That's because he authored a book called "Redemption: The Myth of Pet Overpopulation and the No Kill Revolution in America" that challenges the very foundation of nearly every theory and principle of shelter management in this country: The idea that there are more pets dying in shelters each year than homes available for those pets.

In fact, with between 4 and 5 million dogs and cats being killed in shelters nationwide every year, denying the existence of pet overpopulation seems ridiculous. If there aren't more pets than homes, why are so many animals ending up in shelters in the first place?

Conventional wisdom tells us it's because of irresponsible pet owners who aren't willing to work to keep their pets in their homes. It's a failure of commitment, of caring, and of the human/animal bond. If fewer pets were born, there would be fewer coming into shelters. If people cared more about their pets, they wouldn't give them up so easily, would spay and neuter them so they wouldn't reproduce, and wouldn't let them stray.

That is exactly what I always believed, too, for the nearly 17 years I've been writing about pets. And yet, after reading "Redemption," I don't believe it anymore.

Winograd's argument is simply this: Based on data from the American Veterinary Medical Association, the American Animal Hospital Association, the Pet Food Manufacturers Association, and the latest census, there are more than enough homes for every dog and cat being killed in shelters every year. In fact, when I spoke to him for this article, he told me that there aren't just enough homes for the dogs and cats being killed in shelters. There are more homes for cats and dogs opening each year than there are cats and dogs even entering shelters.

He's not suggesting this is really nothing but a numbers game, though. "When I argue that pet overpopulation is a myth, I'm not saying that we can all go home," he said. "And I'm not saying that there aren't certain people who are irresponsible with their animals. And I'm not saying that there aren't a lot of animals entering shelters. Again, I'm not saying that it wouldn't be better if there were fewer of them being impounded. But it does mean that the problem is not insurmountable and it does mean that we can do something short of killing for all savable animals today."

There is probably nothing Winograd could say that would more inflame the shelter and humane society establishment than calling pet overpopulation a myth. But Winograd doesn't just stop there. In "Redemption," Winograd lays the lion's share of the blame for shelter deaths not on pet owners and communities, but on the management, staff, and boards of directors of the shelters themselves.

"If a community is still killing the majority of shelter animals, it is because the local SPCA, humane society, or animal control shelter has fundamentally failed in its mission," he writes. "And this failure is nothing more than a failure of leadership. The buck stops with the shelter's director."

Redemption makes the case that bad shelter management leads to overcrowding, which is then confused with pet overpopulation. Instead of warehousing and killing animals, shelters, he says, should be using proven, innovative programs to find those homes he says are out there. They should wholeheartedly adopt the movement known as No Kill, and stop using killing as a form of population control.

Mike Fry, the executive director of Animal Ark Shelter in the Minneapolis area, was one of those who had a problem with Winograd's analysis. Interviewing Winograd on his radio show, he said, "I was one of those people, when I saw the title "The Myth of Pet Overpopulation ..." the hackles kind of went up on the back of my neck. This is a problem we're struggling and fighting with literally day in day out in the animal welfare community."

Winograd, who has been in the same trenches himself, responded with some specific examples of the buck stopping at the shelter director's desk. "Let's just look at various animals dying in shelters around the nation today," he said on Fry's radio show. "If ... motherless kittens are killed because the shelter doesn't have a comprehensive foster care program, that's not pet overpopulation. That's the lack of a foster care program.

"If adoptions are low because people are getting those dogs and cats from other places, because the shelter isn't doing outside adoptions (adoptions done off the shelter premises), that's a failure to do outside adoptions, not pet overpopulation.

"And you can go down the list. If animals are killed because working with rescue groups is discouraged, again, that's not pet overpopulation. If dogs are going cage-crazy because volunteers and staff aren't allowed to socialize them, and then those dogs are killed because they're quote-unquote "cage crazy," because the shelter doesn't have a behavior rehabilitation program in place, once again, that's not pet overpopulation; that's the lack of programs and services that save lives.

"And you can say that about feral cats being killed because a shelter doesn't have a trap-neuter-return program. You can say that about shy or scared dogs because the shelter is doing this bogus temperament testing that's killing shy dogs and claiming they are unadoptable. It goes on and on and on."

Winograd's not just talking about something that could happen, but something that has already happened many times in a number of American communities — including San Francisco, which in 1994 became the first city in the United States to end the killing of healthy dogs and cats.

Of course, the San Francisco SPCA was not the first no-kill shelter in the United States. There have always been individual shelters and rescue groups that have not used population control killing. What San Francisco did was to institutionalize No Kill on a county-wide basis, guaranteeing that animals would not be killed simply for lack of shelter space. The SFSPCA promised to take all adoptable, treatable, and rehabilitatable pets that came into San Francisco's municipal shelter, and find homes for them if the city shelter could not.

"If you look at what San Francisco did between 1993 and 1994, the number of deaths didn't decline by one percent or two percent," Winograd said. "In the case of healthy animals it declined 100 percent. In the case of sick and injured animals it declined by about 50 percent." Nonetheless, instead of adopting similar programs for their own communities, most observers of the time shrugged it off, saying that it wouldn't work anywhere else. San Francisco, they said, is special.

As a fourth-generation native, I'm the first to admit my city is special. But the reality is that No Kill has worked in a wide variety of communities. Winograd later left California and took over the SPCA in Tompkins County, N.Y., which held the animal control contract for the region and has an open admissions policy. One of the most compelling sections of "Redemption" tells how Winograd walked into the shelter and, literally overnight, ended the practice of killing for shelter space:

"The day after my arrival, my staff informed me that our dog kennels were full and since a litter of six puppies had come in, I needed to decide who was going to be killed in order to make space. I asked for 'Plan B'; there was none. I asked for suggestions; there were none."

He spoke directly to his staff, saying, "Volunteers who work with animals do so out of sheer love. They don't bring home a paycheck. So if a volunteer says, 'I can't do it,' I can accept that from her. But staff members are paid to save lives. If a paid member of staff throws up her hands and says, 'There's nothing that can be done,' I may as well eliminate her position and use the money that goes for her salary in a more constructive manner. So what are we going to do with the puppies that doesn't involve killing?"

The story of how Tompkins County stopped killing for population control and started sending more than 90 percent of the animals that come into its animal control system out alive may be one of the greatest success stories of the humane movement. It's certainly one of the most compelling parts of the argument laid out in "Redemption."

Because, although it wasn't always easy, these programs worked, and not only in San Francisco or Tompkins County. "In Tompkins County, we reduced the death rate 75 percent in two years. In Charlottesville, Va., they reduced it by over 50 percent in one year. And Reno, Nev. ... has reduced the death rate by over 50 percent," Winograd said.

"If all shelters not only have the desire and embrace the No Kill philosophy, but comprehensively put into play all those programs and services that ... I ... collectively call the no-kill equation, then we would achieve success."

The issue of pet overpopulation is only one piece of the story told in "Redemption." Within its pages, readers and animal lovers can find the blueprint not so much for our failure to save the animals in our communities, but for our ability to start doing so today. It challenges us to demand more of our shelters than the status quo, to insist on an end to the use of killing as a form of animal population control, and tells us to stop allowing our tax dollars and donations to support shelters and animal control agencies that refuse to implement programs that have been proven in communities across America to work to end the killing.

Be sure to visit all our pages for more news, information, and commentary. Take action to help animals!